Military Declares War on Holidays

Pentagon suspends celebrations that honor women and racial and ethnic minorities

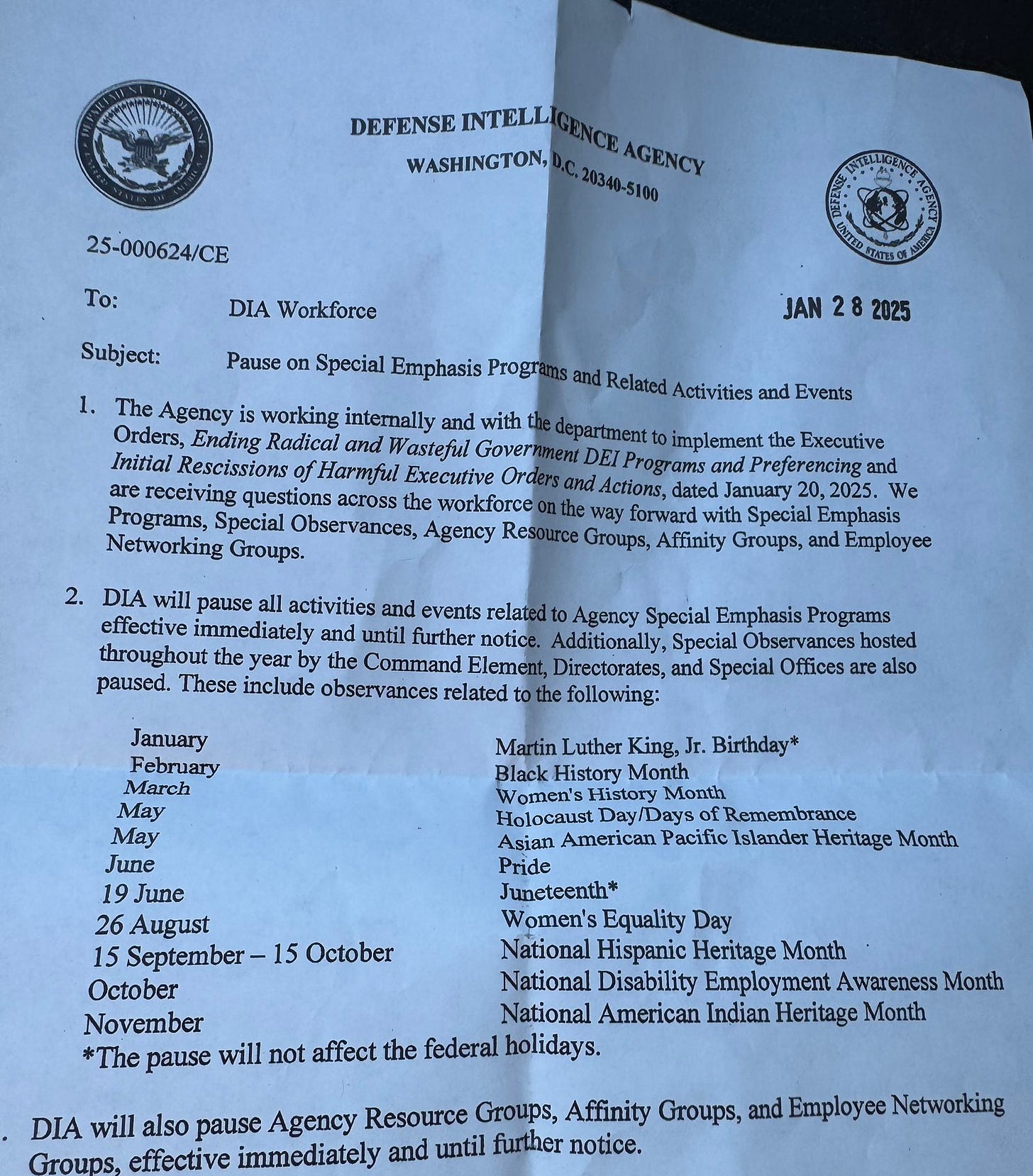

Earlier this week, I reported that the Defense Intelligence Agency ordered staff to suspend all activities and events at work relating to Holocaust remembrance, MLK’s birthday, Juneteenth, and several other “special observances.”

The directive, I can now report, extends to the entire military, as another leaked Army operations order I obtained and the Pentagon now confirms in a public statement late Friday.

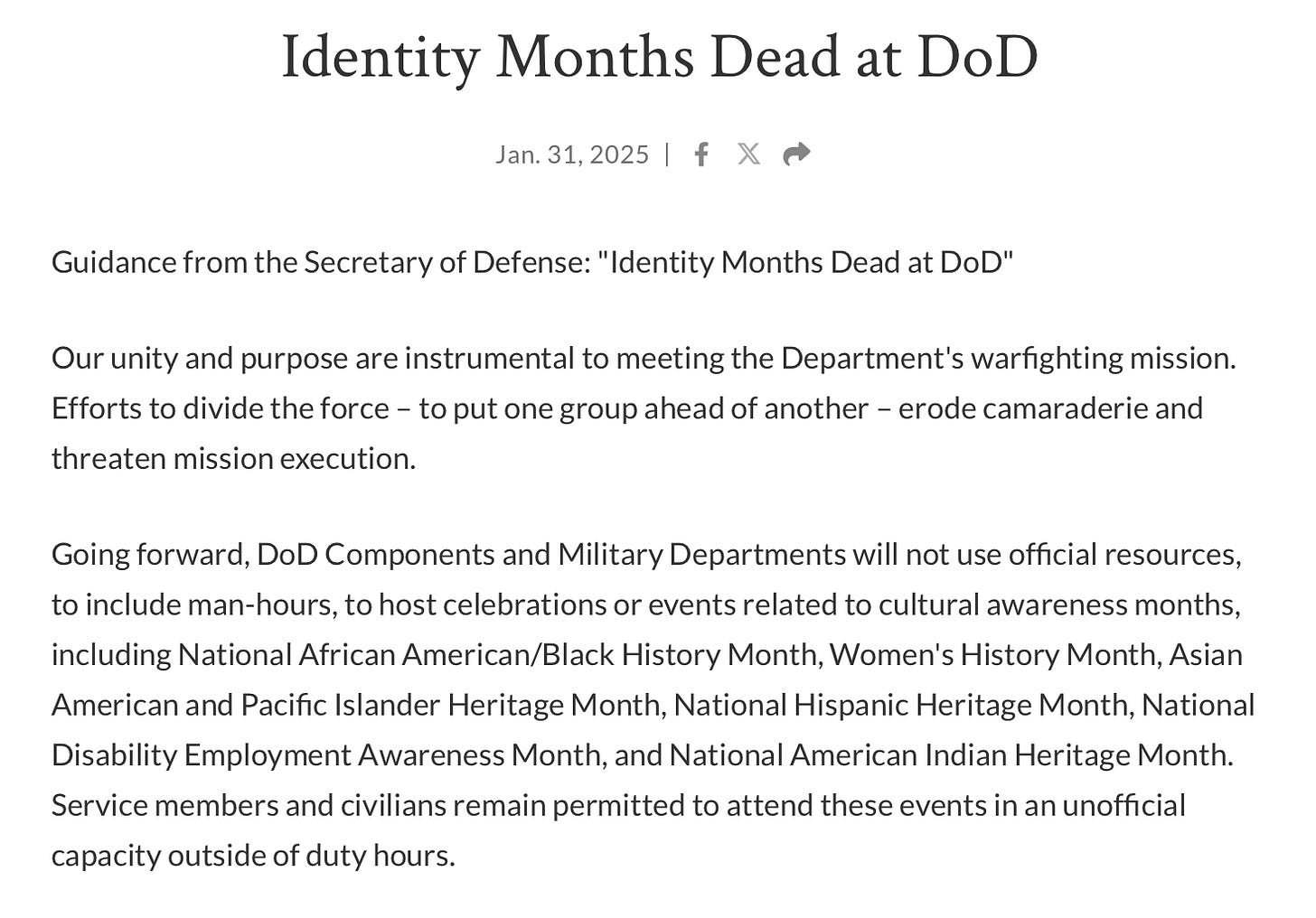

The Pentagon’s public statement, obviously cognizant of the political minefield, dropped the prohibitions on national holidays recognized by law (MLK day and Juneteenth), as well as Pride and the Holocaust. Instead, it focusing on celebrations of ethnic and racial minorities like Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, National African American/Black History Month, and Women's History Month, literally declaring them “dead,” directing that no “official resources, to include man-hours, to host celebrations or events” can be used.

This story began with a tip I received earlier this week from a government worker who said they’d heard the military would no longer allow activities related to Black History Month at work. This is one of hundreds of tips I’ve gotten since the inauguration and while I looked for confirmation, I obtained the Defense Intelligence Agency document corroborating the tip and much more. I had the goods.

I posted the DIA document to social media, to get it out, talking with my editor Bill Arkin that maybe we’d do a full-length story later. I winced a bit, knowing that my Substack readership pays the bills, but there was so much else to cover. And, we decided, our task is to get leaks and documents out to the public as quickly as possible.

My Twitter post promptly went viral and the Associated Press soon did a story. It didn’t credit me. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in going independent, it is that there is a strict divide between the mainstream and social media. First, there’s just a view that social media doesn’t count as journalism. Second, there is a presumption that when something is on social media, it is just a retweet, a post from a post from a post, with no beginning and no end. But this was my scoop and I told the AP reporter, who updated her story to say the document was first published by me.

Actual journalism, the convention goes, is when you tack 900 unnecessary words onto a scoop that often can just be told in a single tweet. Time that could be spent getting more information out to the public is instead spent on following dinosaur practices and keeping up appearances of “confirmation.”

That issue of “confirmation,” of course, feeds much of the disinformation and fact-checking industry. I was reminded of this when I got an email from Snopes, the “fact-checking” website. They said they were trying to authenticate the document I had posted. “I’m attempting to independently verify the memo’s authenticity,” the email explained. At first I was puzzled: the document is right there and the military isn’t denying it. How could this be in dispute?

Next came an ask so audacious I had to laugh: “If you do know the identity of the person who sent you the memo, would you be willing to ask if they’d feel comfortable sharing their information with me?” The thought that I would out my source — a member of the secretive intelligence community with which the Trump administration is openly at war — to someone I didn’t even know was beyond belief. I ignored it, and now my punishment is a Snopes headline declaring the document merely “Alleged” (even though the Pentagon has now officially put out its own confirmation).

The episode is a useful illustration of the problem with the entire “fact checking” enterprise. They may think that they are rooting out disinformation and purifying the public square, but what they do shows they are less interested in the truth and more in authority. Suppose I had shared with them the identity of my source: what does that prove? Nothing other than the person’s officialdom, which is what those places really care about. Snopes would not have asked the same question if The New York Times had published this document.

When I resigned from my job at a mainstream media outlet last May and went public with the dysfunction I had witnessed there, I was leaving behind not just that job but the prospect of any other like it. I did so because I had become convinced that old school journalism conventions were getting in the way of its most essential task: informing as much of the American people as possible.

As the above story illustrates, the rules of journalism — that it has to look a certain way, not just be true — are unnecessary and time consuming. Reporters who live in this journalism 1.0 environment have to thus deal with conventions that force them to get confirmation from the very agencies they are dealing with, then pass a review by multiple layers of managerial bureaucracy, and stuff the article with “context” that insults the intelligence of the reader. By the time the story is published, the outrage is homogenized and the moment has passed. In the current environment, 30 other stories have flashed by during this descent into fruitless paperwork.

None of this is to say I don’t confirm my reporting, relying on my editor’s expertise and judgment, smell tests and other methods. These Trump directives are coming fast and furious, and even here in this little story: the DIA and the Pentagon disagreed as to which holiday celebrations are banned.

The reason I’ve had the time to correspond with many dozens of federal employees this week and share their comments, emails, memos and other insights with you is because I left those conventions and the “process” of old school journalism behind. Federal employees have repeatedly told me that they learn more about what’s going on from my reporting than their own agencies.

I can say that I’ve done what I set out to do: respect the intelligence of my readers by not denying them access to what I know or showing them the documents to see for themselves.

And I’ve learned again that sometimes a full-length story is necessary, like here, to explore ideas too complicated for a tweet. But sometimes it isn’t, like when there’s a blizzard of executive orders people just want to know the basics of.

Please help me continue to tell the difference between these two things by becoming a paid subscriber.

— Edited by William M. Arkin

The fact that this list doesn't include Columbus Day is telling.

You are doing what everyone really wants. I think you are much more valuable than people who have "authority." You don't even try to spin your stuff. You just inform. Keep doing what you're doing. Also, thank you for telling us how the process is designed. They basically want to gatekeep and life moves too fast for that in 2025. For the record, I don't need a woman's appreciation day. I certainly don't want them to spend taxpayer money for celebratory stuff. Just keep us safe. That's all I care about from the military.